Jan 31 2021.

...

Ideal would be 15.04 arcsec/sec of angular rate so that stars are fixed relative to this source. (this is sidereal rate, or in other words, the rate you would get for a 24 hour orbital period) - youd want this rate at the part where its overhead at night. If

1 radian / second = 206,264.806 arc seconds / second ; w = 2pi/T ; newtonian mechanics - How do I convert tangential speed to angular speed in an elliptic orbit? - Physics Stack Exchange ---- or conservation of energy & angular momentum in a comet orbit (duke.edu)

Steo 1: analysis of basic physics-

- for a circular orbit of radius R_orbit, what is apparent angular rate at zenith as seen from ground? Ans- it's v_orbit/(R_sat-R_Earth) in rad/sec. Orbit at 5000 km above-earth orbit has 5 km/s vel so 1 mrad/sec ~ 200 arcsec/sec so 10X sidereal. this means its going really fast, way faster than telescopes can track, cant rotate and resolve fast enough, too blurry. 13.3X sidereal?

- LEO Radius: 2000 km; period is about 90-120 min; so dividing 24 hrs/2 hrs = 12X sidereal rate, roughly; speed of satellites are 28000 km/h → 7 km/s

- geostationary orbit is 35786 km away (+7000 km if counting radius of earth); period is one sidereal day. speed is 3 km/s

- Polar orbits take the satellites over the Earth’s poles. The satellites travel very close to the Earth (as low as 200 km above sea level), so they must travel at very high speeds (nearly 8 km/s).

- R_ earth = 6,378 km at equator, 6,357 km at pole

- M earth = 6 × 10 24 kg

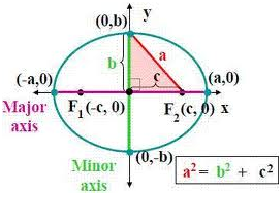

- For an elliptical orbit, conservation of energy implies

v2 = GM(2/r - 1/a) where r is distance to center of mass (i.e. center of Earth) and a is semi-major axis of orbit.

We need v of order 0.6 km/s when r=11,000 km = 1.1e7m to hit the desired angular rate. What's the implied value of a? More generally, what family of orbits does what we want? - this is a back of the envelope calc - this is a rough

- What is the sunlight intensity vs. distance from Earth (umbra vs. penumbra), in the shadow? What is angular size of shadow as seen from observatory? https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Umbra,_penumbra_and_antumbra

- Geometric Aspects | Solar Radiation (greenrhinoenergy.com) - this might help, but have to figure out how to do it for one day and distance from the shadow; however, it varies throughout the year as well

- it also matters where the observatory is placed?

- Energy (a-ghadimi.com) chp 7

- SkyMarvels.com Reference - flux measurements but on earth

- lecture.2.global.energy_cycle (uci.edu) - solar flux at earth

- Geometric Aspects | Solar Radiation (greenrhinoenergy.com) - this might help, but have to figure out how to do it for one day and distance from the shadow; however, it varies throughout the year as well

- Is there a sun-synch orbit that does the right thing? Sun-synch orbits have really high inclinations, like 80 degrees, and precess once per year so the lock plane of the orbit relative to the sun

- Is there a strobed-source approach that would work, if we could make a constant-integrated-photon-flux-per-pulse strobed source? What about scintillation?

Ionospheric scintillation is the rapid modification of radio waves caused by small scale structures in the ionosphere. Severe scintillation conditions can prevent a GPS receiver from locking on to the signal and can make it impossible to calculate a position. Less severe scintillation conditions can reduce the accuracy and the confidence of positioning results .Scintillation of radio waves impacts the power and phase of the radio signal. Scintillation is caused by small-scale (tens of meters to tens of km) structure in the ionospheric electron density along the signal path and is the result of interference of refracted and/or diffracted (scattered) waves. ??

- strobe - regular flashes of light; flicker

...

If fuel became a problem, perhaps we could make a orbit with a 12 hour period but still Molnya, that way we only have to thrust half as much because the rate of precession relative to the orbit will make the orbit symmetric.

Some notes I need to write because I am new to this stuff:

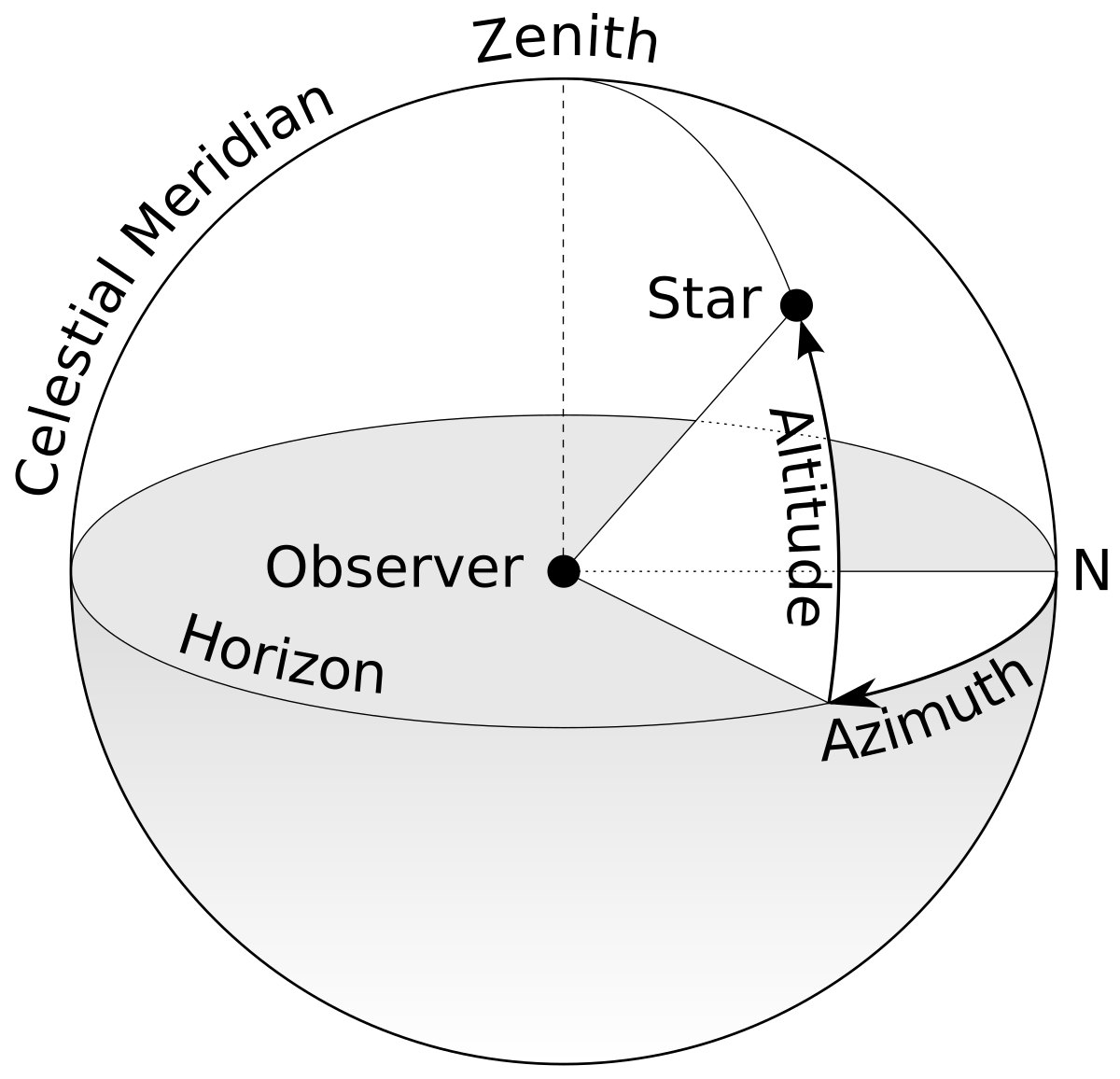

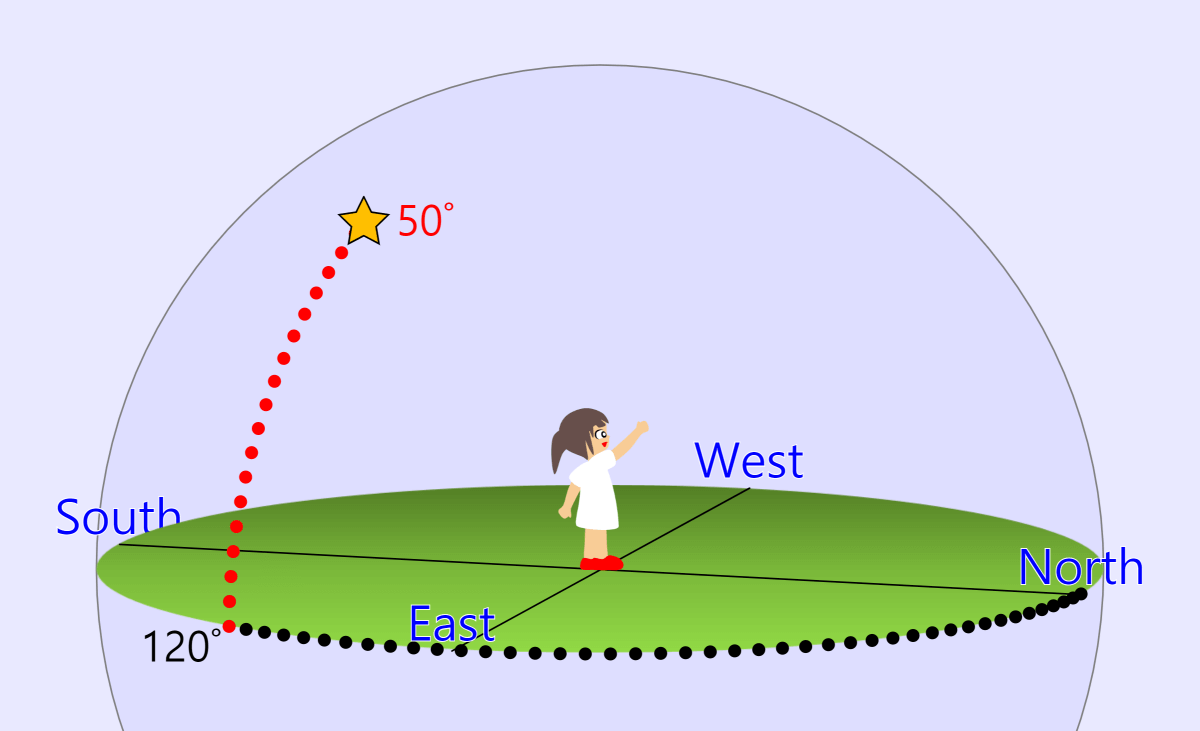

- Altitude (alt.), sometimes referred to as elevation (el.), is the angle between the object and the observer's local horizon. For visible objects, it is an angle between 0° and 90°.

- Alternatively, zenith angle may be used instead of altitude. The zenith angle is the complement of altitude, so that the sum of the altitude and the zenith angle is 90°.

- Azimuth (az.) is the angle of the object around the horizon, usually measured from true north and increasing eastward. Exceptions are, for example, ESO's FITS convention where it is measured from the south and increasing westward, or the FITS convention of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey where it is measured from the south and increasing eastward.

The horizontal coordinate system is sometimes called other names, such as the az/el system,[4] the alt/az system, or the alt-azimuth system, from the name of the mount used for telescopes, whose two axes follow altitude and azimuth

Sun Synchonous - This orbit is a special case of the polar orbit. Like a polar orbit, the satellite travels from the north to the south poles as the Earth turns below it. In a sun-synchronous orbit, though, the satellite passes over the same part of the Earth at roughly the same local time each day (for example, the satellite always shows up at midnight over Cambridge, allowing for easy calibration over it). This can make communication and various forms of data collection very convenient. For example, a satellite in a sun-synchronous orbit could measure the air quality of Ottawa at noon. From the perspective of the sun, the orbit looks exactly the same and does not change as the earth revolves around it. Look at the picture from the perspective of the sun.

However, this means that other areas of the world cant use this calibration quite like the designated area can.

There is a special kind of sun-synchronous orbit called a dawn-to-dusk orbit. In a dawn-to-dusk orbit, the satellite trails the Earth's shadow. When the sun shines on one side of the Earth, it casts a shadow on the opposite side of the Earth. (This shadow is night-time.) Because the satellite never moves into this shadow, the sun's light is always on it (sort of like perpetual daytime). Since the satellite is close to the shadow, the part of the Earth the satellite is directly above is always at sunset or sunrise. That is why this kind of orbit is called a dawn-dusk orbit. This allows the satellite to always have its solar panels in the sun.

Sun-synchronous polar orbit - YouTube - really great video; it should be noted that the orbit of the satellite is LEO, and goes around every 90 minutes around earth, so it would eventually go in front of a lot of parts of earth since the period is so fast; however if we had a molnya orbit we could make it stationary such that we calibrate using a known source about that same 24 hour period.

The inclination is the angle the orbital plane makes when compared with Earth's equator. why do sun synchronous orbit have high inclinations? because it requires less thrust to precess the right amount? Look at sun syncronous wiki for inclination info

So technically, we want a dusk to dawn orbit! At some orbit that is Molnya like such that the angular rate issue is resolved. See new wiki page for details

Precession - In astronomy, precession refers to any of several gravity-induced, slow and continuous changes in an astronomical body's rotational axis or orbital path. Precession is a change in the orientation of the rotational axis of a rotating body. In an appropriate reference frame it can be defined as a change in the first Euler angle, whereas the third Euler angle defines the rotation itself. The sun synchronous orbit slowly precesses around Earth to always be in the dark at a given time over a part of the planet. Formula for precession is here: Sun-synchronous orbit - Wikipedia

Why does it do precession? - It's mostly physics magic! The Earth's rotation causes it to bulge slightly at the equator, which means the Earth is trying to twist the Orbit over on to its side. How this causes the orbit plane to rotate isn't very intuitive, but you can recreate the same effect by spinning up an old bike wheel and holding it on one side of the hub while it is upright. For the Earth's rotation to cause exactly the right rate of precession, we just have to periodically tweak the orbital inclination and altitude. We use around 20kg of fuel per year for this, and that's mainly to tweak the inclination. If we tried to make the orbit turn through the year without the help of the equatorial bulge, we'd burn through our 300kg fuel budget within a few hours!

Angular rate - rate at which the thing moves across the sky. Angular velocity is the rate of velocity at which an object or a particle is rotating around a center or a specific point in a given time period.

Sidereal day just refers to when the earth completes one revolution relative to itself in a vacuum. a solar day it when the same spot on earth faces the sun again. the sidereal rate is the rate at which the earth spins on its axis, and consequently the rate at which the 'fixed' stars appear to move in the sky.A sidereal day – 23 hours 56 minutes and 4.1 seconds – is the amount of time needed to complete one rotation, so there are 4 minutes left that carry over. sidereal time at any given place and time will gain about four minutes against local civil time, every 24 hours, until, after a year has passed, one additional sidereal "day" has elapsed compared to the number of solar days that have gone by.

Using sidereal time, it is possible to easily point a telescope to the proper coordinates in the night sky. Briefly, sidereal time is a "time scale that is based on Earth's rate of rotation measured relative to the fixed stars. This is because you are measuring and going by the absolute rotation of the Earth so the stars must be in the same place every day, not shifted around ever 4 minutes.

In the picture of the sun and distant star above: Sidereal time vs solar time. Above left: a distant star (the small orange star) and the Sun are at culmination, on the local meridian m. Centre: only the distant star is at culmination (a mean sidereal day). Right: a few minutes later the Sun is on the local meridian again. A solar day is complete.

the sidereal rate is the rate at which the earth spins on its axis, and consequently the rate at which the 'fixed' stars appear to move in the sky.

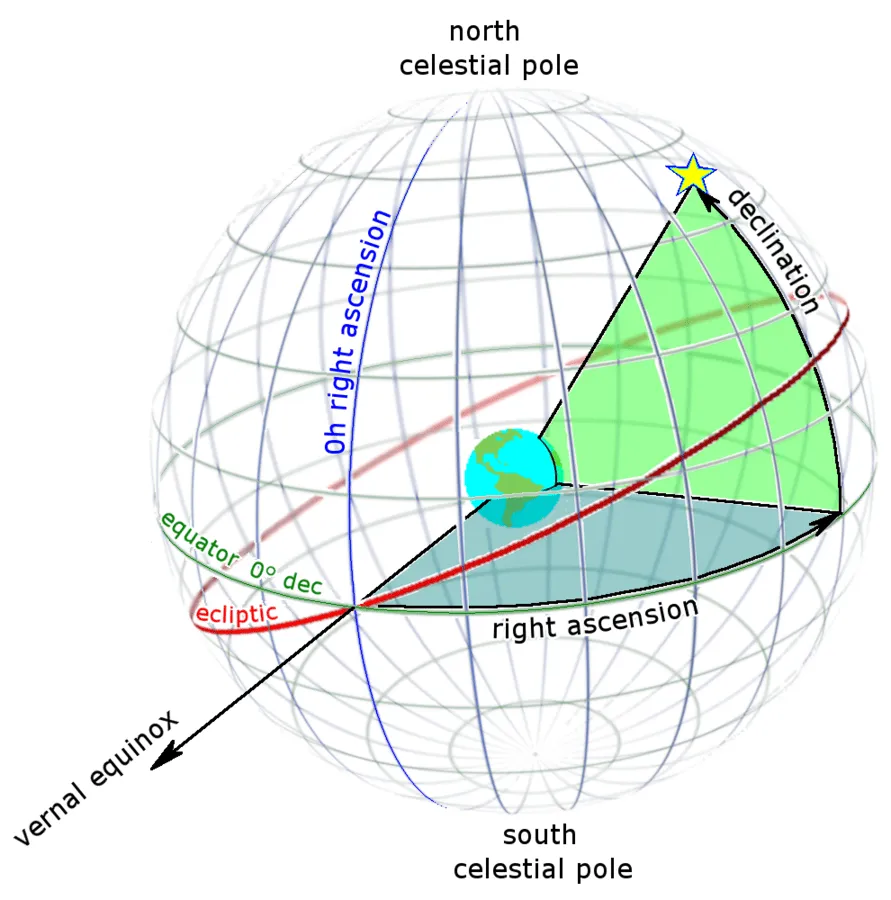

equinox - the time or date (twice each year) at which the sun crosses the celestial equator, when day and night are of equal length (about September 22 and March 20).

The umbra (Latin for "shadow") is the innermost and darkest part of a shadow, where the light source is completely blocked by the occluding body. An observer within the umbra experiences a total eclipse. The penumbra (from the Latin paene "almost, nearly") is the region in which only a portion of the light source is obscured by the occluding body. An observer in the penumbra experiences a partial eclipse. https://mysite.du.edu/~jcalvert/astro/shadows.htm

However, the umbra and penumbra of course aren't just triangles, they're cones; and as such, treat them. Question is : are earth and the sun in the same plane?

- What is the sunlight intensity vs. distance from Earth (umbra vs. penumbra), in the shadow? What is angular size of shadow as seen from observatory? https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Umbra,_penumbra_and_antumbra

- this matters because if we are in the penumbra, some sunlight will come through, defeat the purpose of being a calibration source; or we'd have to subtract that intensity, technically, to get a good reading.

- Is there a strobed-source approach that would work, if we could make a constant-integrated-photon-flux-per-pulse strobed source? What about scintillation?

- wdym?

apparent parallax - an apparent change in the position of an object resulting from a change in position of the observer. astronomy the angle subtended at a celestial body, esp a star, by the radius of the earth's orbit

Parallax makes it seem to move faster than background stars, in opposite direction.

Another way to see how this effect works is to hold your hand out in front of you and look at it with your left eye closed, then your right eye closed. Your hand will appear to move against the background.

This effect can be used to measure the distances to nearby stars. As the Earth orbits the Sun, a nearby star will appear to move against the more distant background stars. Astronomers can measure a star's position once, and then again 6 months later and calculate the apparent change in position. The star's apparent motion is called stellar parallax.

There is a simple relationship between a star's distance and its parallax angle:

d = 1/p

The distance d is measured in parsecs and the parallax angle p is measured in arcseconds.

This simple relationship is why many astronomers prefer to measure distances in parsecs.

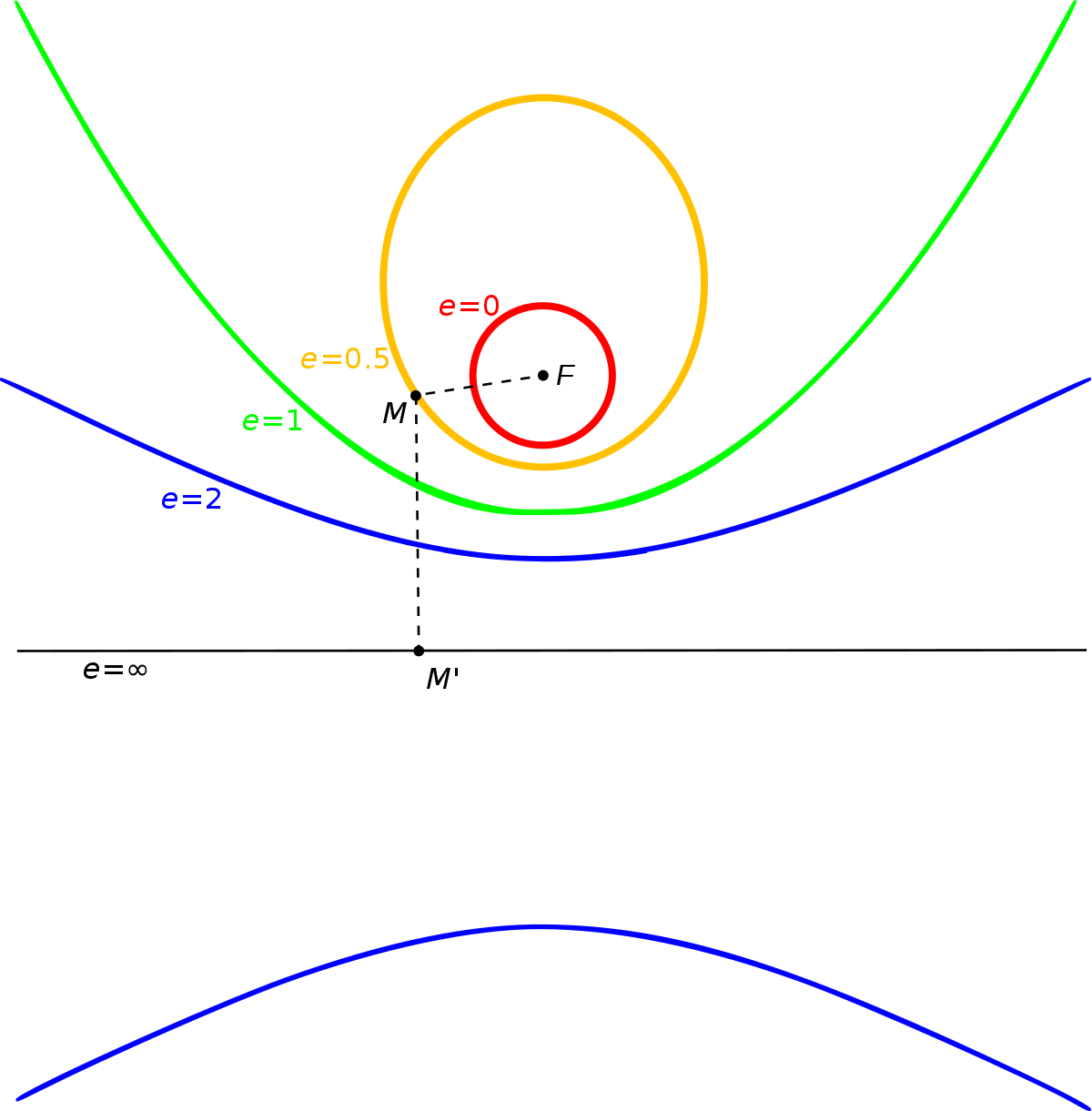

ellipticity vs eccentricity

The orbital eccentricity of an astronomical object is a dimensionless parameter that determines the amount by which its orbit around another body deviates from a perfect circle. A value of 0 is a circular orbit, values between 0 and 1 form an elliptic orbit, 1 is a parabolic escape orbit, and greater than 1 is a hyperbola. Orbital eccentricity - Wikipedia

For elliptical orbits eccentricity e can also be calculated from the periapsis and apoapsis since rp = a(1 − e) and ra = a(1 + e), where a is the semimajor axis. look at wikipedia

Linear speed is the measure of the concrete distance travelled by a moving object. it would be the tangent of the circle in this case.

- we'd be at the focus of the ellipse, and the ellipse is the orbit of the satellite; the fourth picture is the side view of what would be going on, with earth being M. The angular rate at apoapsis needs to be about 15 arcsec/sec, and the period in total needs to be about 24 hrs.

Feb 20, 2021. Stubbs

I thought about this some more. To make an "astro-stationary" orbit, the line of sight between the surface of the Earth and the satellite has to not rotate in inertial space. The only way for that to happen (for simplicity assume satellite overhead at midnight, at its apogee) is to have the velocity components perpendicular to the line of sight at the two ends be equal in both magnitude and direction. That means the satellite tangential velocity has to match that of the Earth's surface, which is a meagre 0.46 km/s. An orbit that does that has a semi-major axis of 2 million km, which makes things awkward in terms of orbital period.

So what can we do? One option is to park the satellite near the L2 Lagrange point (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lagrange_point) , which is on the line that connects the center of the sun to the center of the Earth. That point orbits the sun once per year, and could sit in the Earth's shadow the entire time. It's basically orbiting in the (sun plus Earth) combined potential well, with a period of a year. Problem then is solar panels never see any light. So we'd want a tweaked L2 orbit that goes in and out of the Earth's shadow with about a 50-50 duty cycle. The distance to L2 is about 1.5 M km, and so parallax angular rate due to Earth rotation and finite distance is about theta-dot ~ 0.5 km/s/1.5 e6 km ~ 0.07 arcsec per sec. That's fine.

The other option is to put the satellite in a much closer orbit, and use a strobe system to make light pulses that are short enough that the image doesn't streak.

Since we want the angular size to be comparable to a star's atmospherically blurred image, about 1 arcsec in angular extent, the angle subtended by the telescope aperture D as seen from the satellite at a distance R can't be bigger than one arcsec which means D/R < 5E-6 rad. For LSST, which has a diameter of 8.5m, the minimum distance to the satellite should satisfy R > D/5E-6 > 1.7E6m or R > 1,700 km, from the Earth's surface. That in turn means a semimajor axis of at least Re+1700 or 8000 km. That gives about a 2 hour period, which is kinda nice. The tangential orbital speed is about 7 km/s. When directly overhead that's an apparent angular rate of 7km/s/1700km = 4 mrad/s, or 800 arcsec/s. For the streak length to be less than 1 arc sec, the light flash duration is about 1 msec. One benefit of doing it this way is we can measure emitted photon dose with each flash, and are relieved from doing any accurate shutter timing. The LSST calibration telescope has a field of view of around 6 arcmin = 2 mrad, and so the satellite would take about half a second to transit the field. If the flasher had a 1:5 duty cycle, the flash freq would be about 200 Hz so we'd get about 100 spots of light. Frame subtraction photometry would take out the background stars. One could interleave different color monochromatic sources to get multiband information, flashing them in turn. Encoding a varying flash freq or skipping one every few pulses would synchronize the data sets.

Note this now a cubesat scale project

One big drawback to this approach is atmospheric scintillation, mentioned earlier. Temperature fluctuations drive index variations that drive wavefront distortion. This makes the integrated flux in the pupil jitter around, and is what makes stars twinkle at night. A relevant paper is here Scintillation_MNRAS.pdf and this is a Figure:

The effect scales at telescope diameter D^(-4/3). The plot above is for a 1m diameter telescope, for LSST the effect would be 8.5(-4/3) or twenty times smaller. That makes scintillation a minor component of the error budget.

A quick photon flux estimate: Imagine we had a 1 Watt optical source, broadcasting into 1/4 of 4pi. If it's at a distance of 1000 km then a 1 meter radius collector (2m dia telescope) subtends a surface area fraction of that segment of the sphere that is f= pi*1m^2/(pi*1E6^2) =1E-12 of the illuminated surface area at that distance. That means we'd intercept 1 pW of optical power, which generates (rough numbers) 1 pA of photocurrent. That's a photoelectron rate of 1E-12/1.6E-19 ~ 6 million photons per second.

How bright, in astronomical magnitudes, is this thing? Use sun as a benchmark:

Sun emits around 3.8E26 Watts, at a distance of 150E9 meters. Sun has an apparent magnitude of -26.7. If we made it 1W it becomes 2.5 log (3.8e26) mags fainter, or 66.4 mag fainter, making it mag 39.7. Now move it closer by a factor of 150E9/1e6 = 150E3. Magnitude change is 5*log(D1/D2) which makes our 1 Watt source at a distance of 1000 km be comparable to a star at around 13th apparent magnitude.

That is roughly consistent with this exposure time calculator, for 4 meter DECam system, downloaded from http://www.ctio.noao.edu/noao/content/Exposure-Time-Calculator-ETC

Observing sequence would be:

...

Feb 20, 2021. Stubbs

I thought about this some more. To make an "astro-stationary" orbit, the line of sight between the surface of the Earth and the satellite has to not rotate in inertial space. The only way for that to happen (for simplicity assume satellite overhead at midnight, at its apogee) is to have the velocity components perpendicular to the line of sight at the two ends be equal in both magnitude and direction. That means the satellite tangential velocity has to match that of the Earth's surface, which is a meagre 0.46 km/s. An orbit that does that has a semi-major axis of 2 million km, which makes things awkward in terms of orbital period.

- is this too far for light? also my calcs for where the umbra is differ from what they say here; this means we'd get sunlight contamination: It is, however, slightly beyond the reach of Earth's umbra,[21] so solar radiation is not completely blocked at L2. Spacecraft generally orbit around L2, avoiding partial eclipses of the Sun to maintain a constant temperature. But mine say it is slightly below umbra point so it would be fine.

Tangent vel of line of sight needs to be equal - - - line has to be at the same orientation

Lagrange point - earth orbits the sun w the same period ;;; L2 is in earths shadow ; L2 is not a good place to put thing, line of sight rotates once a year

perturb the thing in a pendulum like thing around L2 so it sees sun; or put a radioisotope generator on there (see if it fits on a cubesat)

So what can we do? One option is to park the satellite near the L2 Lagrange point (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lagrange_point) , which is on the line that connects the center of the sun to the center of the Earth. That point orbits the sun once per year, and could sit in the Earth's shadow the entire time. It's basically orbiting in the (sun plus Earth) combined potential well, with a period of a year. Problem then is solar panels never see any light. So we'd want a tweaked L2 orbit that goes in and out of the Earth's shadow with about a 50-50 duty cycle. The distance to L2 is about 1.5 M km, and so parallax angular rate due to Earth rotation and finite distance is about theta-dot ~ 0.5 km/s/1.5 e6 km ~ 0.07 arcsec per sec. That's fine.

-would other types of energy generation work? or too expensive? and alos do we stay fixed in L2 and leave, how does that work?

The other option is to put the satellite in a much closer orbit, and use a strobe system to make light pulses that are short enough that the image doesn't streak.

Since we want the angular size to be comparable to a star's atmospherically blurred image, about 1 arcsec in angular extent, the angle subtended by the telescope aperture D as seen from the satellite at a distance R can't be bigger than one arcsec which means D/R < 5E-6 rad. For LSST, which has a diameter of 8.5m, the minimum distance to the satellite should satisfy R > D/5E-6 > 1.7E6m or R > 1,700 km, from the Earth's surface. That in turn means a semimajor axis of at least Re+1700 or 8000 km. That gives about a 2 hour period, which is kinda nice. The tangential orbital speed is about 7 km/s. When directly overhead that's an apparent angular rate of 7km/s/1700km = 4 mrad/s, or 800 arcsec/s. For the streak length to be less than 1 arc sec, the light flash duration is about 1 msec. One benefit of doing it this way is we can measure emitted photon dose with each flash, and are relieved from doing any accurate shutter timing. The LSST calibration telescope has a field of view of around 6 arcmin = 2 mrad, and so the satellite would take about half a second to transit the field. If the flasher had a 1:5 duty cycle, the flash freq would be about 200 Hz so we'd get about 100 spots of light. Frame subtraction photometry would take out the background stars. One could interleave different color monochromatic sources to get multiband information, flashing them in turn. Encoding a varying flash freq or skipping one every few pulses would synchronize the data sets.

Note this now a cubesat scale project

One big drawback to this approach is atmospheric scintillation, mentioned earlier. Temperature fluctuations drive index variations that drive wavefront distortion. This makes the integrated flux in the pupil jitter around, and is what makes stars twinkle at night. A relevant paper is here Scintillation_MNRAS.pdf and this is a Figure:

y axis is the scintillation noise (want precision to at least 1%); exposure time

The effect scales at telescope diameter D^(-4/3). The plot above is for a 1m diameter telescope, for LSST the effect would be 8.5(-4/3) or twenty times smaller. That makes scintillation a minor component of the error budget.

A quick photon flux estimate: Imagine we had a 1 Watt optical source, broadcasting into 1/4 of 4pi. If it's at a distance of 1000 km then a 1 meter radius collector (2m dia telescope) subtends a surface area fraction of that segment of the sphere that is f= pi*1m^2/(pi*1E6^2) =1E-12 of the illuminated surface area at that distance. That means we'd intercept 1 pW of optical power, which generates (rough numbers) 1 pA of photocurrent. That's a photoelectron rate of 1E-12/1.6E-19 ~ 6 million photons per second.

How bright, in astronomical magnitudes, is this thing? Use sun as a benchmark:

Sun emits around 3.8E26 Watts, at a distance of 150E9 meters. Sun has an apparent magnitude of -26.7. If we made it 1W it becomes 2.5 log (3.8e26) mags fainter, or 66.4 mag fainter, making it mag 39.7. Now move it closer by a factor of 150E9/1e6 = 150E3. Magnitude change is 5*log(D1/D2) which makes our 1 Watt source at a distance of 1000 km be comparable to a star at around 13th apparent magnitude.

That is roughly consistent with this exposure time calculator, for 4 meter DECam system, downloaded from http://www.ctio.noao.edu/noao/content/Exposure-Time-Calculator-ETC

Observing sequence would be:

figure out (RA, Dec, time) track across the sky from satellite ephemeris

Set desired filter in instrument

point to a place in the sky where it will transit. Make sure shutter is open at the appropriate time.

take images before and after, in same passband

subtract a template from the images. That will show beads-on-a-string sequence of flashes that have same point spread function as stars. Calculate total flux for each flash, compute an appropriate mean.

Then go back to the images with no satellite and do same kind of photometry there. The passband-integrated fluxes of the stars can be calibrated relative to the monochromatic light flashes.

Thinking back to L2 for a moment, same source put there would be 5 log (1000 km/1.5e6 km) = 16 magnitudes fainter. But from there the Earth subtends a small angle, so we could use optical gain to beam the light towards the Earth. Earth angle is 6300 km / 1.5 M km = 4 mrad so making a collimator would get us back to 14th mag pretty easily. One cute idea for the L2 version is to use a radio-isotope power source so it could in fact sit in the Earth's shadow the entire time. The thermal heat generated can be used to keep the thing warm. NASA's MMRTG https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Multi-mission_radioisotope_thermoelectric_generator generates 2 kW thermal and ~100 W electrical at end of life. Mass is 45 kg. That way we totally avoid any thermal shocks that would accompany an eclipsing orbit and it's observable 100% of the time.

Cond: 1 remains in shaodow of earth - make sure its this all yr long - line of sight roatoes once a year, if semi major axis roatoes once a yr, sun- synched (this differs from L2 by 40 millarcsecs) - 40 milliarcsec/sec

2: fixed relative to stars

favoriable line of sight roates in sky once a yr

L2 is far, cant charge

pendulum idea not nice

check it, see if agree

are there orbits that werent considered

Check answers

Ion thrusters too?

equatorial vs ecliptic? equatorila easier

| orbit | vel at apogee | Range at apogee, from observatory | ~Zenith Apparent Angular rate; for the earth not rotating | isotropic source range dilution | min airmass range | period | airmass change in 1 hour | time visible above 20 deg | differential angular rate rel to stars - satellite - earth motion parallax effect | time spent in 10 arcmin FOV imager that is tracking the sky | CW or strobed source(s)? | notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L2 a=1.5 M km in ecliptic plane | approx 30 km/s but the around sun | 1.5 M km | 40 milliarcsec/sec - relative to the stars ; ideal ang rate is 0, fixed to stars | 1.3 E-6 - not feasible unelss idea above (optical gain reflector, ) | seasonal variation between abs(latitude+/-23.5) | NA | 15 degrees, 0.04 airmass delta | all night, all year | 40 milliarcsec/sec plus any L2 dynamics | inf. | CW | long integration will work requires RTG if always in shadow |

a=8000 km circular inclination = 23.5 deg | 7 km/s | 1.7 K km | 820 arcsec/sec - goldilocks, circular so it doesnt need to precess; may be helpful if strobed (100s of flashes) | 1 | (need to figure this out) | 2 hours | horizon to horizon | 15 min per rev for overhead pass | 820 arcsec/s | 0.7 sec | strobed at 1 msec on-time. Scintillation is a concern. - adaptive optics, forget it | no need to engineer precession |

a=16000 km e=0.6 inclination = 23.5 deg | 5 km/s | 20 K km | 70 arcsec/sec | 7.2E-3 | seasonal variation between abs(latitude+/-23.5) | 5.6 hours | 55 degrees, 0.7 airmass delta | ~ 3 hours (check this, likely longer) | ~ 55 arcsec/s- -ang rate sint so high, drifts across not as fast, bc of earth rotation ; goldilocks sol | 11 min | strobed at 10 msec on-time, alternating with CW. | sun-synch attainable for elliptical orbit, min propulsion needed |

| geosynch a=42.1 K km | 3 km/s | 42.1 K km | zero - its in sunshine ,out | 2.6E-3 | fixed airmass | 24 hours | zero. apparent alt-az fixed | all night, all year | 15 arcsec/sec | 40 min | strobed | reflected sunlight at 1.3 kW /m^2 competes single satellite awkward for both Hawaii and Chile can't be seen from S pole |

| LEO- 500 km altitude circular | 7.6 km/s | few hundred km - too fast | 0.87 deg/sec = 3100 arcsec/s; too fast unless you strobe source | 11.5 | all airmasses exercised | 1.5 hours | horizon to horizon | 5 min | 3100 arcsec/s | 0.2 sec - transits to the fild is too fast, whips by | uh, it's a problem. | sunsynch orbit is nearly polar. Essentially need to track the satellite. |

Telescope tracking systems are typically designed to provide optimum tracking performance at sidereal rates (~15 arcsec/sec). However, LEO objects have extremely large angular velocities that can exceed sidereal rates by a factor of 10. Many telescopes can slew at much higher angular velocities, but they do not have the tracking accuracy or large field of view (FOV) needed to keep a fast moving LEO target within the FOV of the imaging camera. Many RSOs also have low radar cross sections that result in low apparent brightness. These factors make small LEO and distant GEO targets very difficult to acquire and detect against the background photon flux.

of radius R_orbit, what is apparent angular rate at zenith as seen from ground? Ans- it's v_orbit/(R_sat-R_Earth) in rad/sec. Orbit at 5000 km above-earth orbit has 5 km/s vel so 1 mrad/sec ~ 200 arcsec/sec so 10X sidereal. this means its going really fast, way faster than telescopes can track, cant rotate and resolve fast enough, too blurry. 13.3X sidereal?

- velocity at apogee = done, in code

- range at apogee =done, in code

- apparent angular rate, fixed = can do

- v_tangential / height_above_earth, where v_tangential is at apogee, and height_above_earth=r_sat-r_earth (at apogee). That will give you an answer in rad/s → convert to arcsec/sec by multiplying it by 1 rad = 206264.806 arcsec.

- isotropic source range dilution = ???

- min airmass range = ???

- period =done , in code

- airmass change in 1 hour = ???

- time visible above 20 deg = ???

- How Ephemerides are Calculated (caltech.edu)

- orbit - Calculating Which Satellite Passes are Visible - Space Exploration Stack Exchange

- take the diff relative angular rate, divide by 10 arcmin (600 arcsec), take the reciporcal of that to get minutes

- How Ephemerides are Calculated (caltech.edu)

- differential angular rate rel to stars = idk , maybe subtract by 3-5 arcsec/sec?

- Parallax makes it seem to move faster than background stars, in opposite direction. Typical parallax rate is 3 to 5 arcsec per sec. If we have orbital rate of ~20 arcsec per sec going the other way, it's locked to the stars.

- Differential rotation is seen when different parts of a rotating object move with different angular velocities (rates of rotation) at different latitudes and/or depths of the body and/or in time. This indicates that the object is not solid

time visible

refs

Adaptive optics guide star and calibration satellite, ORCAS:

...

MIT PhD dissertation on artificial guide star