Jan 31 2021.

The objective of this project is to assess orbit choices for an orbiting calibration source. There are two things we desire: 1) satellite is in the shadow of the Earth, so that we avoid reflected sunlight issues, and 2) angular rate not to exceed 30 arcsec/sec, i.e. twice the sidereal rate, so that large telescopes can track the source easily. Two limiting cases that don't work: i) geosynch orbits put source at fixed azimuth and elevation (angluar rate =0) but except for equinox these objects are in the sunlight, ii) low earth orbits, few 100 km above surface, are in shadow but have really high angular rate as seen from observatory.

Ideal would be 15.04 arcsec/sec of angular rate so that stars are fixed relative to this source. (this is sidereal rate, or in other words, the rate you would get for a 24 hour orbital period) - youd want this rate at the part where its overhead at night. If

1 radian / second = 206,264.806 arc seconds / second ; w = 2pi/T ; newtonian mechanics - How do I convert tangential speed to angular speed in an elliptic orbit? - Physics Stack Exchange ---- or conservation of energy & angular momentum in a comet orbit (duke.edu)

Steo 1: analysis of basic physics-

- for a circular orbit of radius R_orbit, what is apparent angular rate at zenith as seen from ground? Ans- it's v_orbit/(R_sat-R_Earth) in rad/sec. Orbit at 5000 km above-earth orbit has 5 km/s vel so 1 mrad/sec ~ 200 arcsec/sec so 10X sidereal. this means its going really fast, way faster than telescopes can track, cant rotate and resolve fast enough, too blurry. 13.3X sidereal?

- LEO Radius: 2000 km; period is about 90-120 min; so dividing 24 hrs/2 hrs = 12X sidereal rate, roughly; speed of satellites are 28000 km/h → 7 km/s

- geostationary orbit is 35786 km away (+7000 km if counting radius of earth); period is one sidereal day. speed is 3 km/s

- Polar orbits take the satellites over the Earth’s poles. The satellites travel very close to the Earth (as low as 200 km above sea level), so they must travel at very high speeds (nearly 8 km/s).

- R_ earth = 6,378 km at equator, 6,357 km at pole

- M earth = 6 × 10 24 kg

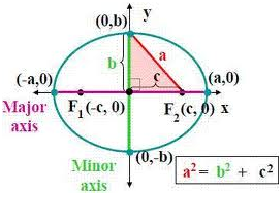

- For an elliptical orbit, conservation of energy implies

v2 = GM(2/r - 1/a) where r is distance to center of mass (i.e. center of Earth) and a is semi-major axis of orbit.

We need v of order 0.6 km/s when r=11,000 km = 1.1e7m to hit the desired angular rate. What's the implied value of a? More generally, what family of orbits does what we want? - this is a back of the envelope calc - this is a rough

- What is the sunlight intensity vs. distance from Earth (umbra vs. penumbra), in the shadow? What is angular size of shadow as seen from observatory? https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Umbra,_penumbra_and_antumbra

- Geometric Aspects | Solar Radiation (greenrhinoenergy.com) - this might help, but have to figure out how to do it for one day and distance from the shadow; however, it varies throughout the year as well

- it also matters where the observatory is placed?

- Energy (a-ghadimi.com) chp 7

- SkyMarvels.com Reference - flux measurements but on earth

- lecture.2.global.energy_cycle (uci.edu) - solar flux at earth

- Geometric Aspects | Solar Radiation (greenrhinoenergy.com) - this might help, but have to figure out how to do it for one day and distance from the shadow; however, it varies throughout the year as well

- Is there a sun-synch orbit that does the right thing? Sun-synch orbits have really high inclinations, like 80 degrees, and precess once per year so the lock plane of the orbit relative to the sun

- Is there a strobed-source approach that would work, if we could make a constant-integrated-photon-flux-per-pulse strobed source? What about scintillation?

Ionospheric scintillation is the rapid modification of radio waves caused by small scale structures in the ionosphere. Severe scintillation conditions can prevent a GPS receiver from locking on to the signal and can make it impossible to calculate a position. Less severe scintillation conditions can reduce the accuracy and the confidence of positioning results .Scintillation of radio waves impacts the power and phase of the radio signal. Scintillation is caused by small-scale (tens of meters to tens of km) structure in the ionospheric electron density along the signal path and is the result of interference of refracted and/or diffracted (scattered) waves. ??

- strobe - regular flashes of light; flicker

** Need to be sure to include the apparent parallax due to motion of the Earth's surface, under the satellite.

Parallax makes it seem to move faster than background stars, in opposite direction. Typical parallax rate is 3 to 5 arcsec per sec. If we have orbital rate of ~20 arcsec per sec going the other way, it's locked to the stars. So do we want 15 or 20 arcsec/sec? - we want it to be 15 arcsec/sec (mismatch of a facotr of 2 is ok (up to twice the rate is ok

steps:

- pick an ellipticity between 0.5 and 0.9

- for semi-major axis "a" ranging from 7,000 km to 20,000 km

- figure out where the focus of ellipse is, call that "c"

- compute distance to center of mass when satellite is at apogee, which is r=c+a

- compute linear speed at that point in the orbit, using expression above

- compute apparent angular rate from orbital motion, in radians per sec that is v/r

- convert to arcsec per sec

- compute apparent parallax due to rotation of the Earth

- compute inclination of orbit needed to attain sun-synch precession

- produce plots of

- apogee speed vs a ; tangential speed - but why do we care about this when angular rate gives us same info?; a bit of a pain; textbooks on astrodynamics ; at aphelion and perihelion, speeds are at right angles - gmm/r = mv^2/r is the only place in the worbit where this is true

- apogee angular rate vs a - yes

- parallax at apogee vs. a - does this have to do with angle itself, like what we see it? ; i dont get what im plotting here if you sat at elliptical focus, it is the instaneous tang rate / radius - but we are not sitting on the focus ; the cetner of the earth is the focus, parallax effect at equator is maximal; at north pole ; can use this parallax effect to compensate for motion; when its not at its farthest position the velcoty vector is smaller -where in the highly elliptical orbit ; plane will be in the equatorial plane;

- highly elliptical orbit at the distances needed it will be at the equatorial plane ; dist of satellite div by ; rate is what we care about not the

- north pole line of sight is 0 but line of sight is moving more at eqautor

- astrodynamics text - rate of precession of the orbit if the orbit is equatiorial - you get closed orbit ffrom a mass that is spherically symmetric - as soon as the mass deparets from symmetry the way that it's squished makes the satellite get attacted to the earth more; that attraction accelerates the orbit

- the reason a lot are polar and LEO is that they are trying to reduce the rate of precession .

- we need it to precess once per year. needs to be damn near

There are two alternatives:

- natural precession, where inclination angle of orbit depends on both semi-major axis and ellipticity. That will induce North-South motion that's awkward.

- use propellant to induce orbit precession, where the orbit can now lie in the equatorial plane. That way we stand a chance of matching the angular rate of background stars

- how much propellant? roughy 2pi*a/year = 6*10,000 km/(365*24*3600) ~ few m/s per year. Could be a good application for an ion thruster.

Another question is what orbital plane?

- equatorial plane?

- ecliptic plane? (I favor this one)

I think there might be a good solution with e=0.60, a=16,000 km. The sun-synch orbit is almost equatorial, rather than polar.

That puts the range-to-focus at apogee to be a*(1+e)=1.6*16000km, and distance from Earth surface of about 20,000 km.

A beam launched at the Earth with a divergence of 1 arcsec would make a spot of size 4.86E-6*20e6m= 100m. Wow, not bad!

geomview -run savi on MAC to run simulator.

How far does satellite have to be in order to have apparent angular size of below half an arcsec, comparable to size from atmospheric seeing? theta=D_telescope/R_satellite ~ 2 E-6 radians.

For a 30 meter diameter telescope, require R>D_tel/theta > (30 x 10^6)/2 ~ 15,000 km.

If fuel became a problem, perhaps we could make a orbit with a 12 hour period but still Molnya, that way we only have to thrust half as much because the rate of precession relative to the orbit will make the orbit symmetric.

Some notes I need to write because I am new to this stuff:

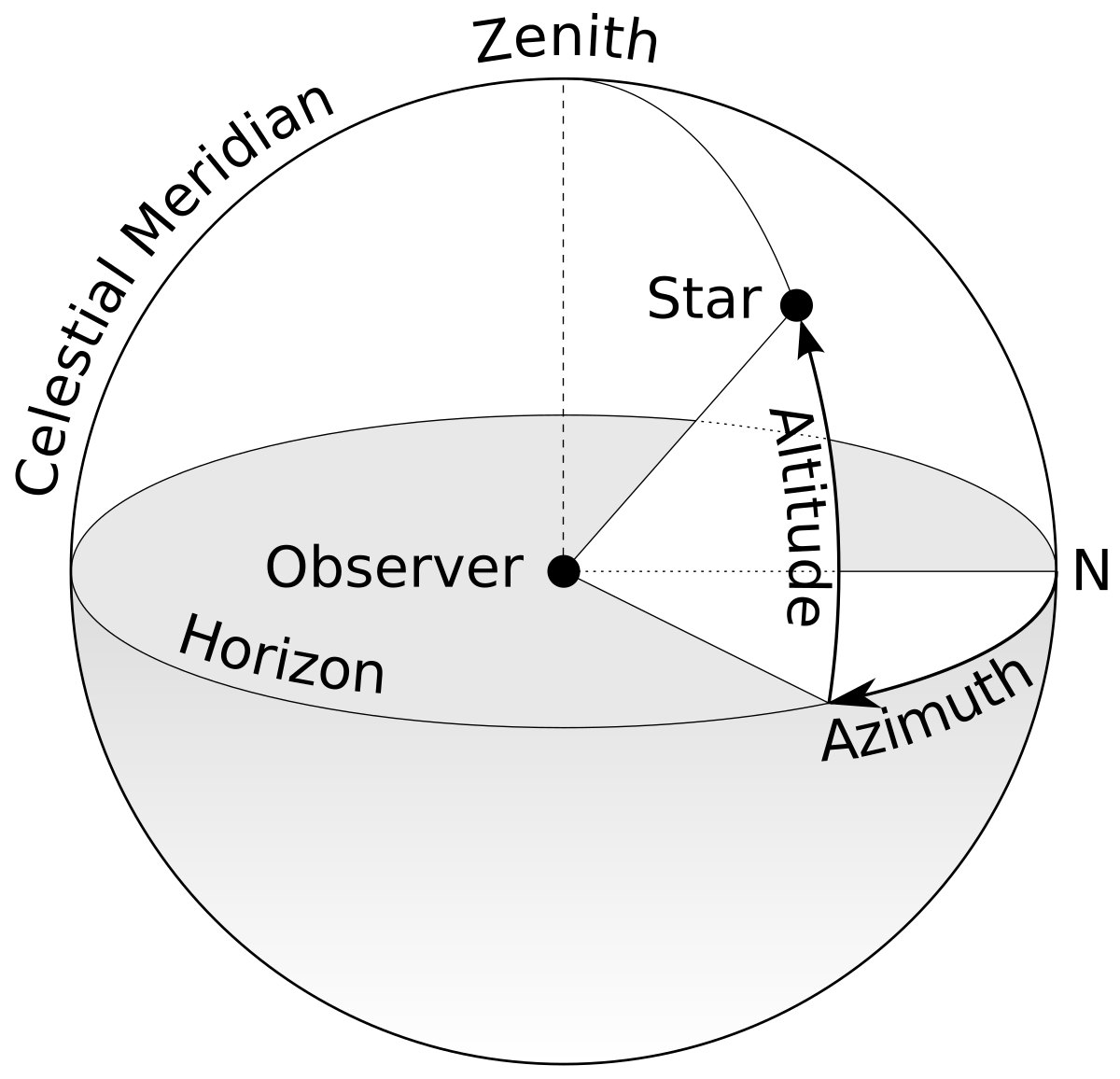

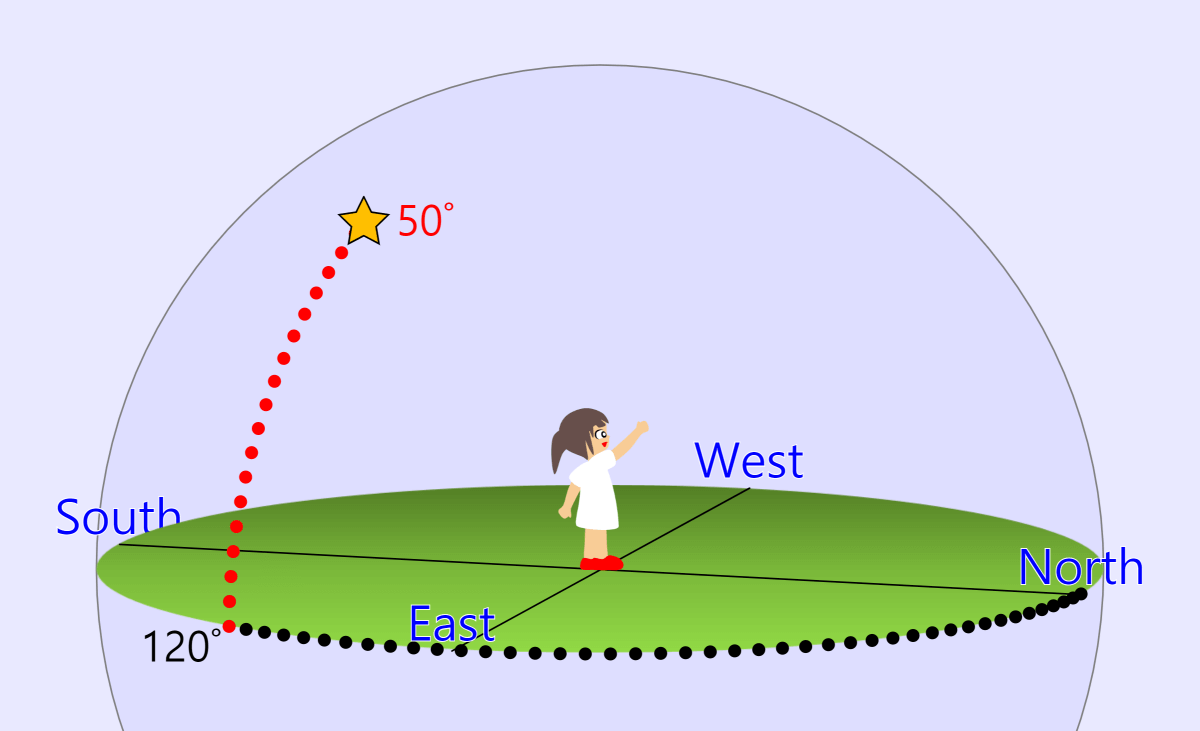

- Altitude (alt.), sometimes referred to as elevation (el.), is the angle between the object and the observer's local horizon. For visible objects, it is an angle between 0° and 90°.

- Alternatively, zenith angle may be used instead of altitude. The zenith angle is the complement of altitude, so that the sum of the altitude and the zenith angle is 90°.

- Azimuth (az.) is the angle of the object around the horizon, usually measured from true north and increasing eastward. Exceptions are, for example, ESO's FITS convention where it is measured from the south and increasing westward, or the FITS convention of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey where it is measured from the south and increasing eastward.

The horizontal coordinate system is sometimes called other names, such as the az/el system,[4] the alt/az system, or the alt-azimuth system, from the name of the mount used for telescopes, whose two axes follow altitude and azimuth

Sun Synchonous - This orbit is a special case of the polar orbit. Like a polar orbit, the satellite travels from the north to the south poles as the Earth turns below it. In a sun-synchronous orbit, though, the satellite passes over the same part of the Earth at roughly the same local time each day (for example, the satellite always shows up at midnight over Cambridge, allowing for easy calibration over it). This can make communication and various forms of data collection very convenient. For example, a satellite in a sun-synchronous orbit could measure the air quality of Ottawa at noon. From the perspective of the sun, the orbit looks exactly the same and does not change as the earth revolves around it. Look at the picture from the perspective of the sun.

However, this means that other areas of the world cant use this calibration quite like the designated area can.

There is a special kind of sun-synchronous orbit called a dawn-to-dusk orbit. In a dawn-to-dusk orbit, the satellite trails the Earth's shadow. When the sun shines on one side of the Earth, it casts a shadow on the opposite side of the Earth. (This shadow is night-time.) Because the satellite never moves into this shadow, the sun's light is always on it (sort of like perpetual daytime). Since the satellite is close to the shadow, the part of the Earth the satellite is directly above is always at sunset or sunrise. That is why this kind of orbit is called a dawn-dusk orbit. This allows the satellite to always have its solar panels in the sun.

Sun-synchronous polar orbit - YouTube - really great video; it should be noted that the orbit of the satellite is LEO, and goes around every 90 minutes around earth, so it would eventually go in front of a lot of parts of earth since the period is so fast; however if we had a molnya orbit we could make it stationary such that we calibrate using a known source about that same 24 hour period.

The inclination is the angle the orbital plane makes when compared with Earth's equator. why do sun synchronous orbit have high inclinations? because it requires less thrust to precess the right amount? Look at sun syncronous wiki for inclination info

So technically, we want a dusk to dawn orbit! At some orbit that is Molnya like such that the angular rate issue is resolved. See new wiki page for details

Precession - In astronomy, precession refers to any of several gravity-induced, slow and continuous changes in an astronomical body's rotational axis or orbital path. Precession is a change in the orientation of the rotational axis of a rotating body. In an appropriate reference frame it can be defined as a change in the first Euler angle, whereas the third Euler angle defines the rotation itself. The sun synchronous orbit slowly precesses around Earth to always be in the dark at a given time over a part of the planet. Formula for precession is here: Sun-synchronous orbit - Wikipedia

Why does it do precession? - It's mostly physics magic! The Earth's rotation causes it to bulge slightly at the equator, which means the Earth is trying to twist the Orbit over on to its side. How this causes the orbit plane to rotate isn't very intuitive, but you can recreate the same effect by spinning up an old bike wheel and holding it on one side of the hub while it is upright. For the Earth's rotation to cause exactly the right rate of precession, we just have to periodically tweak the orbital inclination and altitude. We use around 20kg of fuel per year for this, and that's mainly to tweak the inclination. If we tried to make the orbit turn through the year without the help of the equatorial bulge, we'd burn through our 300kg fuel budget within a few hours!

Angular rate - rate at which the thing moves across the sky. Angular velocity is the rate of velocity at which an object or a particle is rotating around a center or a specific point in a given time period.

Sidereal day just refers to when the earth completes one revolution relative to itself in a vacuum. a solar day it when the same spot on earth faces the sun again. the sidereal rate is the rate at which the earth spins on its axis, and consequently the rate at which the 'fixed' stars appear to move in the sky.A sidereal day – 23 hours 56 minutes and 4.1 seconds – is the amount of time needed to complete one rotation, so there are 4 minutes left that carry over. sidereal time at any given place and time will gain about four minutes against local civil time, every 24 hours, until, after a year has passed, one additional sidereal "day" has elapsed compared to the number of solar days that have gone by.

Using sidereal time, it is possible to easily point a telescope to the proper coordinates in the night sky. Briefly, sidereal time is a "time scale that is based on Earth's rate of rotation measured relative to the fixed stars. This is because you are measuring and going by the absolute rotation of the Earth so the stars must be in the same place every day, not shifted around ever 4 minutes.

In the picture of the sun and distant star above: Sidereal time vs solar time. Above left: a distant star (the small orange star) and the Sun are at culmination, on the local meridian m. Centre: only the distant star is at culmination (a mean sidereal day). Right: a few minutes later the Sun is on the local meridian again. A solar day is complete.

the sidereal rate is the rate at which the earth spins on its axis, and consequently the rate at which the 'fixed' stars appear to move in the sky.

equinox - the time or date (twice each year) at which the sun crosses the celestial equator, when day and night are of equal length (about September 22 and March 20).

The umbra (Latin for "shadow") is the innermost and darkest part of a shadow, where the light source is completely blocked by the occluding body. An observer within the umbra experiences a total eclipse. The penumbra (from the Latin paene "almost, nearly") is the region in which only a portion of the light source is obscured by the occluding body. An observer in the penumbra experiences a partial eclipse. https://mysite.du.edu/~jcalvert/astro/shadows.htm

However, the umbra and penumbra of course aren't just triangles, they're cones; and as such, treat them. Question is : are earth and the sun in the same plane?

- What is the sunlight intensity vs. distance from Earth (umbra vs. penumbra), in the shadow? What is angular size of shadow as seen from observatory? https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Umbra,_penumbra_and_antumbra

- this matters because if we are in the penumbra, some sunlight will come through, defeat the purpose of being a calibration source; or we'd have to subtract that intensity, technically, to get a good reading.

- Is there a strobed-source approach that would work, if we could make a constant-integrated-photon-flux-per-pulse strobed source? What about scintillation?

- wdym?

apparent parallax - an apparent change in the position of an object resulting from a change in position of the observer. astronomy the angle subtended at a celestial body, esp a star, by the radius of the earth's orbit

Parallax makes it seem to move faster than background stars, in opposite direction.

Another way to see how this effect works is to hold your hand out in front of you and look at it with your left eye closed, then your right eye closed. Your hand will appear to move against the background.

This effect can be used to measure the distances to nearby stars. As the Earth orbits the Sun, a nearby star will appear to move against the more distant background stars. Astronomers can measure a star's position once, and then again 6 months later and calculate the apparent change in position. The star's apparent motion is called stellar parallax.

There is a simple relationship between a star's distance and its parallax angle:

d = 1/p

The distance d is measured in parsecs and the parallax angle p is measured in arcseconds.

This simple relationship is why many astronomers prefer to measure distances in parsecs.

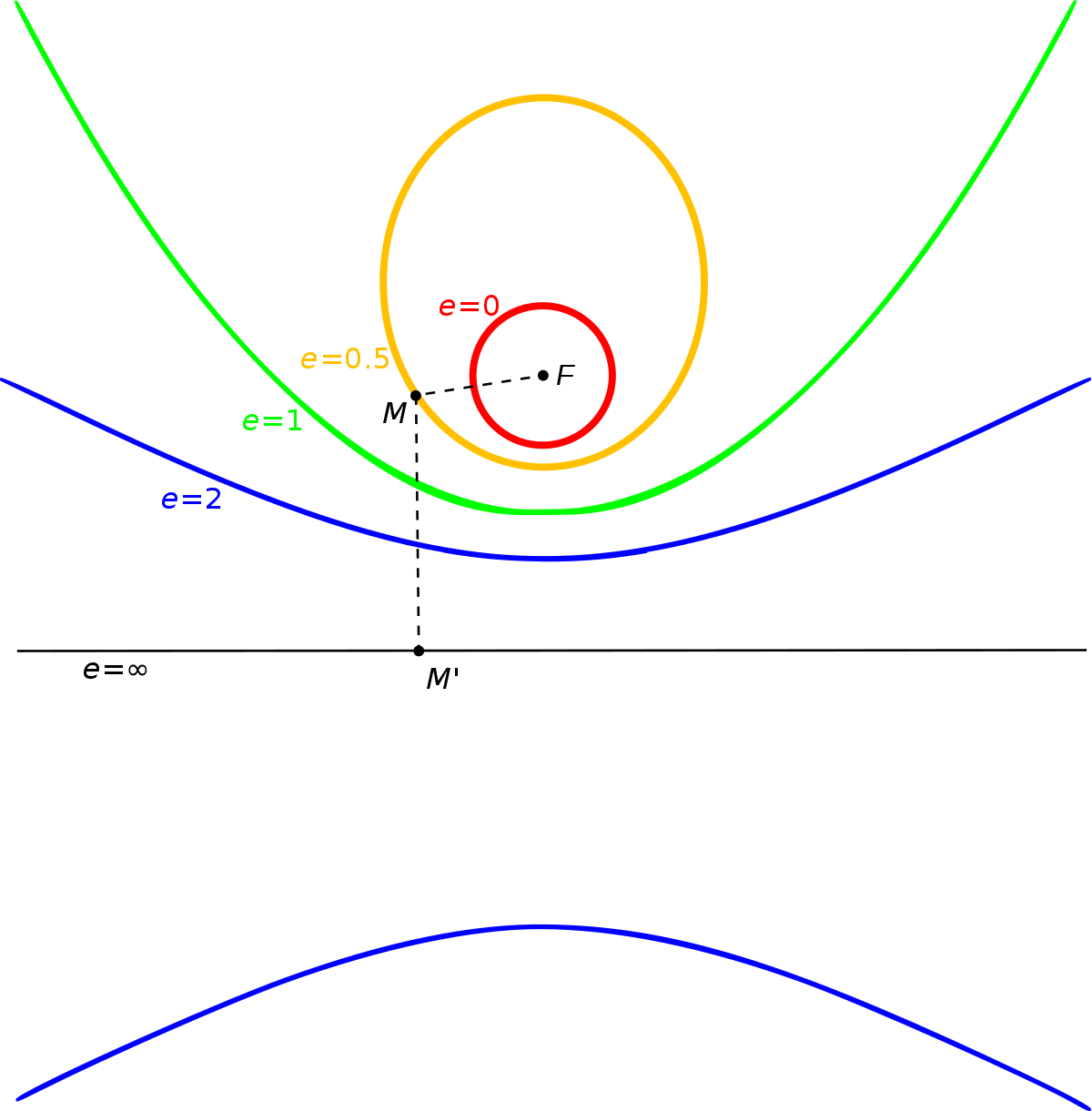

ellipticity vs eccentricity

The orbital eccentricity of an astronomical object is a dimensionless parameter that determines the amount by which its orbit around another body deviates from a perfect circle. A value of 0 is a circular orbit, values between 0 and 1 form an elliptic orbit, 1 is a parabolic escape orbit, and greater than 1 is a hyperbola. Orbital eccentricity - Wikipedia

For elliptical orbits eccentricity e can also be calculated from the periapsis and apoapsis since rp = a(1 − e) and ra = a(1 + e), where a is the semimajor axis. look at wikipedia

Linear speed is the measure of the concrete distance travelled by a moving object. it would be the tangent of the circle in this case.

- we'd be at the focus of the ellipse, and the ellipse is the orbit of the satellite; the fourth picture is the side view of what would be going on, with earth being M. The angular rate at apoapsis needs to be about 15 arcsec/sec, and the period in total needs to be about 24 hrs.

Feb 20, 2021. Stubbs

I thought about this some more. To make an "astro-stationary" orbit, the line of sight between the surface of the Earth and the satellite has to not rotate in inertial space. The only way for that to happen (for simplicity assume satellite overhead at midnight, at its apogee) is to have the velocity components perpendicular to the line of sight at the two ends be equal in both magnitude and direction. That means the satellite tangential velocity has to match that of the Earth's surface, which is a meagre 0.46 km/s. An orbit that does that has a semi-major axis of 2 million km, which makes things awkward in terms of orbital period.

- is this too far for light? also my calcs for where the umbra is differ from what they say here; this means we'd get sunlight contamination: It is, however, slightly beyond the reach of Earth's umbra,[21] so solar radiation is not completely blocked at L2. Spacecraft generally orbit around L2, avoiding partial eclipses of the Sun to maintain a constant temperature. But mine say it is slightly below umbra point so it would be fine.

So what can we do? One option is to park the satellite near the L2 Lagrange point (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lagrange_point) , which is on the line that connects the center of the sun to the center of the Earth. That point orbits the sun once per year, and could sit in the Earth's shadow the entire time. It's basically orbiting in the (sun plus Earth) combined potential well, with a period of a year. Problem then is solar panels never see any light. So we'd want a tweaked L2 orbit that goes in and out of the Earth's shadow with about a 50-50 duty cycle. The distance to L2 is about 1.5 M km, and so parallax angular rate due to Earth rotation and finite distance is about theta-dot ~ 0.5 km/s/1.5 e6 km ~ 0.07 arcsec per sec. That's fine.

-would other types of energy generation work? or too expensive? and alos do we stay fixed in L2 and leave, how does that work?

The other option is to put the satellite in a much closer orbit, and use a strobe system to make light pulses that are short enough that the image doesn't streak.

Since we want the angular size to be comparable to a star's atmospherically blurred image, about 1 arcsec in angular extent, the angle subtended by the telescope aperture D as seen from the satellite at a distance R can't be bigger than one arcsec which means D/R < 5E-6 rad. For LSST, which has a diameter of 8.5m, the minimum distance to the satellite should satisfy R > D/5E-6 > 1.7E6m or R > 1,700 km, from the Earth's surface. That in turn means a semimajor axis of at least Re+1700 or 8000 km. That gives about a 2 hour period, which is kinda nice. The tangential orbital speed is about 7 km/s. When directly overhead that's an apparent angular rate of 7km/s/1700km = 4 mrad/s, or 800 arcsec/s. For the streak length to be less than 1 arc sec, the light flash duration is about 1 msec. One benefit of doing it this way is we can measure emitted photon dose with each flash, and are relieved from doing any accurate shutter timing. The LSST calibration telescope has a field of view of around 6 arcmin = 2 mrad, and so the satellite would take about half a second to transit the field. If the flasher had a 1:5 duty cycle, the flash freq would be about 200 Hz so we'd get about 100 spots of light. Frame subtraction photometry would take out the background stars. One could interleave different color monochromatic sources to get multiband information, flashing them in turn. Encoding a varying flash freq or skipping one every few pulses would synchronize the data sets.

Note this now a cubesat scale project

One big drawback to this approach is atmospheric scintillation, mentioned earlier. Temperature fluctuations drive index variations that drive wavefront distortion. This makes the integrated flux in the pupil jitter around, and is what makes stars twinkle at night. A relevant paper is here Scintillation_MNRAS.pdf and this is a Figure:

The effect scales at telescope diameter D^(-4/3). The plot above is for a 1m diameter telescope, for LSST the effect would be 8.5(-4/3) or twenty times smaller. That makes scintillation a minor component of the error budget.

A quick photon flux estimate: Imagine we had a 1 Watt optical source, broadcasting into 1/4 of 4pi. If it's at a distance of 1000 km then a 1 meter radius collector (2m dia telescope) subtends a surface area fraction of that segment of the sphere that is f= pi*1m^2/(pi*1E6^2) =1E-12 of the illuminated surface area at that distance. That means we'd intercept 1 pW of optical power, which generates (rough numbers) 1 pA of photocurrent. That's a photoelectron rate of 1E-12/1.6E-19 ~ 6 million photons per second.

How bright, in astronomical magnitudes, is this thing? Use sun as a benchmark:

Sun emits around 3.8E26 Watts, at a distance of 150E9 meters. Sun has an apparent magnitude of -26.7. If we made it 1W it becomes 2.5 log (3.8e26) mags fainter, or 66.4 mag fainter, making it mag 39.7. Now move it closer by a factor of 150E9/1e6 = 150E3. Magnitude change is 5*log(D1/D2) which makes our 1 Watt source at a distance of 1000 km be comparable to a star at around 13th apparent magnitude.

That is roughly consistent with this exposure time calculator, for 4 meter DECam system, downloaded from http://www.ctio.noao.edu/noao/content/Exposure-Time-Calculator-ETC

Observing sequence would be:

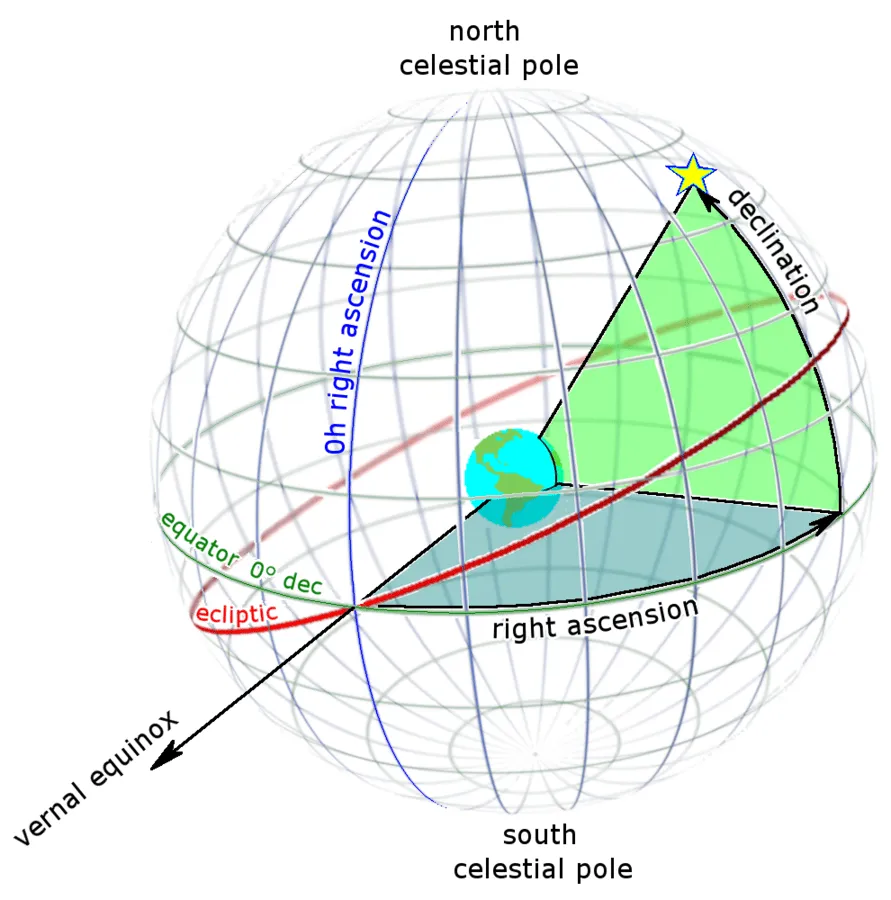

figure out (RA, Dec, time) track across the sky from satellite ephemeris

Set desired filter in instrument

point to a place in the sky where it will transit. Make sure shutter is open at the appropriate time.

take images before and after, in same passband

subtract a template from the images. That will show beads-on-a-string sequence of flashes that have same point spread function as stars. Calculate total flux for each flash, compute an appropriate mean.

Then go back to the images with no satellite and do same kind of photometry there. The passband-integrated fluxes of the stars can be calibrated relative to the monochromatic light flashes.

Thinking back to L2 for a moment, same source put there would be 5 log (1000 km/1.5e6 km) = 16 magnitudes fainter. But from there the Earth subtends a small angle, so we could use optical gain to beam the light towards the Earth. Earth angle is 6300 km / 1.5 M km = 4 mrad so making a collimator would get us back to 14th mag pretty easily. One cute idea for the L2 version is to use a radio-isotope power source so it could in fact sit in the Earth's shadow the entire time. The thermal heat generated can be used to keep the thing warm. NASA's MMRTG https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Multi-mission_radioisotope_thermoelectric_generator generates 2 kW thermal and ~100 W electrical at end of life. Mass is 45 kg. That way we totally avoid any thermal shocks that would accompany an eclipsing orbit and it's observable 100% of the time.

| orbit | vel at apogee | Range at apogee, from observatory | ~Zenith Apparent Angular rate | isotropic source range dilution | min airmass range | period | airmass change in 1 hour | time visible above 20 deg | differential angular rate rel to stars | time spent in 10 arcmin FOV imager that is tracking the sky | CW or strobed source(s)? | notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L2 a=1.5 M km in ecliptic plane | approx 30 km/s but the around sun | 1.5 M km | 40 milliarcsec/sec | 1.3 E-6 | seasonal variation between abs(latitude+/-23.5) | NA | 15 degrees, 0.04 airmass delta | all night, all year | 40 milliarcsec/sec plus any L2 dynamics | inf. | CW | long integration will work requires RTG if always in shadow |

a=8000 km circular inclination = 23.5 deg | 7 km/s | 1.7 K km | 820 arcsec/sec | 1 | (need to figure this out) | 2 hours | horizon to horizon | 15 min per rev for overhead pass | 820 arcsec/s | 0.7 sec | strobed at 1 msec on-time. Scintillation is a concern. | no need to engineer precession |

a=16000 km e=0.6 inclination = 23.5 deg | 5 km/s | 20 K km | 70 arcsec/sec | 7.2E-3 | seasonal variation between abs(latitude+/-23.5) | 5.6 hours | 55 degrees, 0.7 airmass delta | ~ 3 hours (check this, likely longer) | ~ 55 arcsec/s | 11 min | strobed at 10 msec on-time, alternating with CW. | sun-synch attainable for elliptical orbit, min propulsion needed |

| geosynch a=42.1 K km | 3 km/s | 42.1 K km | zero | 2.6E-3 | fixed airmass | 24 hours | zero. apparent alt-az fixed | all night, all year | 15 arcsec/sec | 40 min | strobed | reflected sunlight at 1.3 kW /m^2 competes single satellite awkward for both Hawaii and Chile can't be seen from S pole |

| LEO- 500 km altitude circular | 7.6 km/s | few hundred km | 0.87 deg/sec = 3100 arcsec/s | 11.5 | all airmasses exercised | 1.5 hours | horizon to horizon | 5 min | 3100 arcsec/s | 0.2 sec | uh, it's a problem. | sunsynch orbit is nearly polar. Essentially need to track the satellite. |

refs

Adaptive optics guide star and calibration satellite, ORCAS:

https://asd.gsfc.nasa.gov/orcas/events/Aug2020/agenda/

other papers:

References

sun-synch orbits, including elliptical

MIT PhD dissertation on artificial guide star